History and Use: 12 Principles of Animation

What are Disney’s 12 Principles of Animation?

When you think of wildly successful animation, one of the first studios that comes to mind is Disney. From the original Mickey Mouse all the way through their newest feature film, Disney knows how to create successful animations. While their creative teams are brilliant and new talent gives Disney and its affiliates fresh takes on animation, Disney has a strong foundation with 12 guiding principles of animation.

A Brief History of the 12 Principles of Animation

Walt Disney called the original animators the “Nine Old Men.” They were the core animators, the hands behind some of the most famous animation films created — films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Lady and the Tramp, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, the classic Disney movies audiences have loved for generations.

Two of the core animators, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas, created the 12 principles of animation, making it “an essential must-learn for all aspiring and working animators.” The principles first appeared in their book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation in 1981, but all of the “Nine Old Men” agreed that these principles had been part of their work since the 1930s.

Animators at Disney have been subscribing to these principles ever since. That’s almost a century of these principles living and breathing behind every one of Disney’s animated projects.

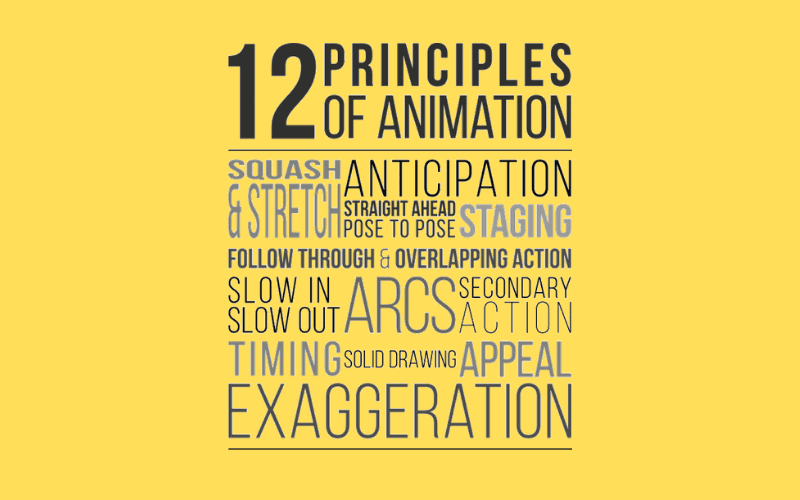

Disney’s 12 Principles of Animation

While there is a lot to be said about each of these principles, we’ll give you the nutshell version.

Squash and stretch

This is an illusion that helps us as the audience visualize the impact gravity has. A character is expanded and compressed, making them appear as if they are moving naturally. In the Pixar Short Day and Night, the two characters are clearly stretched and squashed as they move across the screen, helping us see their movement and dancing.

Anticipation

As an animator, you want to give your audience clues that something big is going to happen — not necessarily a big moment in the story, but a big “action.” It’s like taking a deep breath before a plunge or like Hercules pulling his arm back before he punches Hades in the face.

Staging

Every movement, every pose, should “convey a clear intention.” Freeze the frame on any character, and you should be able to determine what they are feeling. For example, when Belle is talking to Gaston about reading, freeze the frame. You can instantly tell she’s annoyed.

Straight ahead and pose to pose

We’ll break this down into two parts. First, straight ahead. This is when an animator draws one frame after another, creating the movement as they go. This is used when an animator wants to create something fluid, like when Cinderella’s dress is magicked onto her by the Fairy Godmother.

Second, pose to pose. Think of this as taking a character from one position to another that is drastically different, and then filling in the movement in-between. Prince Phillip leans over Aurora’s bed then kisses her. The poses would be leaning over the bed, then him meeting her lips. Pose to pose fills in the movement between.

Follow through and overlapping action

When a character is moving and then stops, their whole body doesn’t stop at once. Some parts of a character will move faster than others, like clothes. When a princess twirls in her dress, the dress moves faster than her body and continues spinning even after her body has stopped.

Slow-in and slow-out

Also essential for adding realism, this is important when characters are moving. An animator will “draw more frames at the start of the action, less frames in the middle, and more frames at the end.”

Arc

This is the idea that almost all actions have a slightly circular motion to them. When you turn your head, you don’t just go straight in or straight out. It curves around.

Secondary Action

Smaller actions are used to support the main action. For example, when Pocahontas runs through the forest, her body is performing the main action, but her hair flapping in the wind is secondary. It enhances the primary action through more movement.

Timing

Many cartoons destroy the laws of physics. But it’s an animator’s job to trick their audience into thinking that it does. Adjusting the timing of a scene—making it slower or smother with more frames, or faster and crisper with less frames—adds to this dimension. Like Dash running on water in The Incredibles.

Exaggeration

Overstating a movement helps prove a point and increase the emotion of a scene but without destroying believability. Like when a character raises their eyebrows or drops their jaw in disbelief.

Solid Drawings

This one is an important reminder that while your medium is 2D, it needs to look 3D to your audience. Keep the same perspective and stay consistent. This helps your believability.

Appeal

While not every character is going to look lovely and cuddly (you need a nasty villain once in a while), it’s still important to create something beautiful. This almost feels like a “duh,” but remember that you want to turn out something clear, easy to read, and personable.

Applying The 12 Principles as a Student

When you’re an animator, it’s your job to create something believable and beautiful. Audiences want to be transported into your world from the opening scene. Following these 12 principles will help you succeed in our Animation Program. Here are three tips you can use to start implementing the 12 principles as a student or new animator:

1. Review them often. Before, during, and after a project, go through this checklist. Did you implement all 12? If not, why not?

2. Look for examples. Watch a Disney movie (or another studio) once a week and look for these principles. You could even keep a journal of what you see to reference later.

3. Ask others to check your work. Ask your peers or a mentor to take a look at your project as you go. Tell them you’re specifically asking for feedback on the 12 principles of animation. Take their critique, and improve on the ones you might have missed.

There are so many ideas and opinions on what makes great animation, but these 12 principles have stood the test of time and millions of frames of animation. By taking them to heart, you’ll have a great chance at success.